Summary

The narrative that Paul Kagame and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) ended the 1994 Tutsi genocide by “defeating genocidal forces” is a carefully orchestrated but contestable construction.

Promoted by Kagame’s regime and echoed by some international observers, this myth oversimplifies the complex dynamics of the Rwandan civil war and genocide.

Drawing on analyses by Allan J. Kuperman and other sources, this article deconstructs this narrative along three axes: the nature of the RPF’s military operations, its strategic refusal of a ceasefire, and the atrocities committed by the RPF before and during the genocide.

This analysis reveals that the RPF, fully aware that its pre-genocide conquest strategy made the genocide inevitable given the circumstances, prioritized seizing power over stopping the massacres, calling into question its image as a “savior.”

Introduction

The 1994 genocide, which claimed approximately 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu lives, is often associated with the military victory of Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), portrayed as having halted the “genocidal forces.”

Amplified by the Rwandan regime and supported by a guilt-ridden international community, this narrative relies on a simplification of events.

A rigorous deconstruction, based on academic works like those of Allan J. Kuperman (2001) and testimonies from defectors, shows that the RPF pursued a military and political strategy prioritizing power acquisition at a catastrophic human cost it had anticipated.

This article examines three key aspects: the nature of the RPF’s combat, its refusal of a ceasefire, and allegations of crimes committed by the RPF, exposing the contradictions in the myth of Kagame as a “savior.”

1. The Nature of the Fighting: Civil War Against the FAR, Not Genocidal Militias

The RPF’s official narrative presents its military victories as a fight against “genocidal forces,” a term encompassing the Interahamwe militias and extremist elements of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR).

However, a critical analysis shows that the RPF primarily fought the regular Rwandan army, which was not inherently genocidal.

According to Allan J. Kuperman (2001) in The Limits of Humanitarian Intervention: Genocide in Rwanda, the RPF’s operations aimed at territorial and political conquest rather than directly stopping the massacres perpetrated by militias.

The FAR, engaged in a civil war against the RPF since 1990, was a conventional military force, not the primary actor in the genocidal killings, which were largely orchestrated by the Interahamwe.

The Interahamwe militias, operating with light weapons (machetes, rudimentary rifles) in local contexts, were often far from the military fronts where the RPF clashed with the FAR.

Thus, the RPF’s victory, culminating in the capture of Kigali in July 1994, disrupted the Rwandan state more than it halted the massacres.

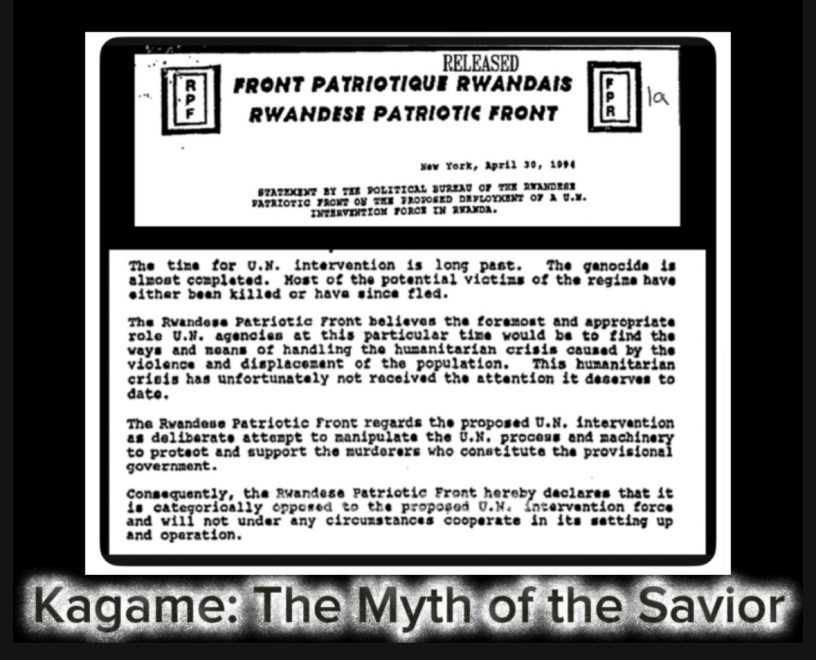

Roméo Dallaire, commander of UNAMIR, references a 30 April 1994 RPF statement indicating that the genocide was “practically complete” by that date, as “there were no more Tutsis left to kill in many regions” (Dallaire, 2003), while categorically refusing the deployment of UN forces.

« The time for U.N. Intervention is long past. The genocide is almost completed.Most of the potential victims of the regime have either been killed or have since fled. »

This suggests that the exhaustion of targets and the flight of genocidaires played a more significant role than direct RPF action.

2. The Refusal of a Ceasefire: A Strategy to Prolong the War

A central element in deconstructing the myth is the RPF’s refusal to accept a ceasefire during the genocide, despite international calls for de-escalation.

In his analysis, Kuperman (2001) argues that the RPF, led by Paul Kagame, rejected ceasefire proposals because such an agreement would have frozen military fronts, preventing the RPF from seizing power by force.

This strategy reflects a deliberate political and military calculation.

Kagame conditioned any ceasefire on terms he knew were impossible, notably the cessation of massacres.

While morally justifiable on the surface, this demand was unrealistic in context.

The massacres, carried out under a so-called “civil self-defense” program, were a direct response to the offensive of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), the RPF’s military wing, and the escalation of the civil war.

Demanding an end to the massacres without first halting the armed conflict was tantamount to setting an impossible condition, as the two phenomena were intrinsically linked.

By imposing these unattainable conditions, Kagame could appear to accept a ceasefire while pursuing his military objectives.

This maneuver allowed him to shift the blame for refusing a truce onto his adversaries while continuing the offensive to seize power.

According to Kuperman, this strategy illustrates the RPF’s willingness to prioritize military victory at all costs, over a negotiated solution that could have reduced human losses.

Testimonies from RPF defectors confirm that Kagame was aware that continuing the civil war, even at the cost of increased massacres, offered a strategic opportunity to conquer Rwanda.

This choice had tragic consequences: by prolonging the war, the RPF indirectly allowed the Interahamwe militias to continue their killings in uncontrolled areas.

3. RPF Atrocities: A Powder Keg Before the Genocide

The deconstruction of the myth is bolstered by allegations of crimes committed by the RPF before and during the genocide.

Paul Kagame knew that the massacres perpetrated by the RPF before the genocide—particularly the killing of nearly 40,000 Hutu civilians in February 1993—as well as targeted political assassinations and infiltrations orchestrated by the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI), sowed indescribable chaos in Rwanda.

These actions, according to reports like MSF-Crash (1995), turned the country into a “powder keg” that the 6 April 1994 assassination of the Rwandan president was sufficient to ignite.

Far from ignoring the likely consequences of this strategy, Kagame knowingly accepted the cost—namely, the genocide of internal Tutsis.

The RPF’s operations, by exacerbating ethnic divisions and fueling fear and mistrust, created conditions ripe for an uncontrollable escalation of violence.

By pursuing an aggressive military strategy that massively violated humanitarian law and the laws of war, Kagame prioritized power acquisition, even at a catastrophic human cost.

This decision, described by some observers as selfish and criminal, reflects the RPF’s prioritization of its political and military objectives over the preservation of stability and civilian lives.

As MSF-Crash (1995) notes, “under General Kagame’s leadership, the RPF engaged in organized killings of Hutus before, during, and after the Tutsi genocide,” undermining the image of a morally irreproachable movement.

4. The Construction and Instrumentalization of the Myth

The myth that Kagame “stopped the genocide” is a narrative construction designed to legitimize his authoritarian rule and deflect criticism.

This narrative has been amplified by international guilt over the failure to intervene in 1994.

As Mediapart (2019) notes, “Paul Kagame has made the Rwandan genocide his stock-in-trade,” using the memory of victims to justify his policies and military interventions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Institutions like the Campaign Against Genocide Museum in Rwanda celebrate the RPF’s victory while glossing over its atrocities.

Dissident voices, such as Tutsi journalist Jean-Pierre Mugabe, denounce this rewriting of history, accusing Kagame of manipulating the genocide narrative to consolidate power.

This instrumentalization marginalizes critics under the pretext of “denialism,” reinforcing Kagame’s authoritarian control while benefiting from the support of Western powers sensitive to his reconstruction discourse.

Conclusion

Deconstructing the myth of Paul Kagame and the RPF as “saviors” requires dismantling historical simplifications.

The works of Allan J. Kuperman, combined with those of Gérard Prunier and others, show that the RPF, having made the genocide inevitable, prioritized seizing power over stopping the massacres.

By refusing a ceasefire and focusing on the regular army rather than the militias, the RPF prolonged the civil war, allowing the killings to continue.

The RPF’s atrocities, including the massacres of Hutu civilians and DMI infiltrations, contributed to creating a powder keg before the genocide, the human cost of which Kagame accepted.

This analysis does not deny the responsibility of Hutu extremists in the genocide but calls for a more lucid reading of Rwandan history.

By exposing the contradictions of the official narrative, this article seeks justice for the victims by preventing their memory from being instrumentalized.

As Kuperman (2001) emphasizes, a faster international intervention could have limited the genocide’s scale, but Kagame’s strategic choices shaped a Rwanda where military victory took precedence over reconciliation.

References

- Dallaire, R. (2003). Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Toronto: Random House Canada.

- Kuperman, A. J. (2001). The Limits of Humanitarian Intervention: Genocide in Rwanda. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- MSF-Crash. (1995). Report on Violence in Rwanda. Paris: Médecins Sans Frontières.

- Prunier, G. (1995). The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mediapart. (2019). “Paul Kagame has made the Rwandan genocide his stock-in-trade.”

- ICTR Archives detailing infiltrations, political assassinations, use of the agafuni, and the decision to assassinate President Habyarimana – epoche.fr/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/archives-tpir-rwanda.pdf

- Spanish Indictment detailing the February 1993 massacres perpetrated by the RPF – epoche.fr/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spanish_indictment.pdf