« Progressivism » is often brandished as a banner of virtue. However, the label does not guarantee the essence.

An idea stamped as « progressive » does not necessarily embody progress.

Today, a segment of progressive discourse promotes a vision where individual identity, elevated to an untouchable core, would exempt the individual from any need for adaptation.

This stance, seductive on the surface, leads to a cognitive and social deadlock, weakening both the individual and the collective.

The Sacralization of Identity: A Refusal to Adapt

Certain contemporary discourses argue that individual identity—beliefs, particularities, idiosyncrasies—possesses an almost tangible reality, an inalienable essence that must be preserved at all costs.

According to this logic, society’s mission is to accommodate all expressions of identity, even the most extreme, and all ideas, even the most foolish, without ever requiring adaptation, which is perceived as an attack on the individual’s integrity.

This reification of identity grants each person absolute centrality, where any demand for evolution or integration of new perspectives is equated with violence against their « treasured » identity.

This logic culminates in the theory of microaggressions, which encourages interpreting every unpleasant feeling, even fleeting, as an implicit aggression.

The « microaggressor, » often unaware, is urged to reform, while the « microaggressed » is encouraged to cultivate hypersensitivity, elevated to a virtue.

Far from protecting, this valorization of fragility exempts the individual from resilience in social interactions, rendering them dependent on an artificially adjusted environment tailored to their singularities.

Adaptation: A Vital Process, Not an Alienation

Refusing adaptation is to misunderstand a fundamental principle of life.

As biology illustrates, an organism that ceases to adapt to its environment would perish.

The cell membrane ensures individuality while allowing essential exchanges.

Similarly, the individual, by opening themselves to new ways of thinking, enriches their identity rather than dissolving it.

In Piagetian terminology, accommodation—the integration of new perspectives—is essential to cognitive development.

Karl Popper, in The Open Society and Its Enemies, emphasizes that a society prospers through critical exchange and the incorporation of new ideas (Popper, 1979, pp. 248, 271).

Rejecting this dynamic condemns the individual to intellectual stasis and society to atrophy.

Pushed to the extreme, the claim to a « right not to adapt » leads to a paradox: by sacralizing particularisms, humanity is deprived of its capacity to reinvent itself.

Far from creating a haven for singularity, a society that exempts the individual from adaptation engenders a world where thought withers, exchange fades, and the collective risks decline.

A society that strives to accommodate every individual idiosyncrasy without ever requiring the slightest adaptation would create an environment where the individual ceases to distinguish their being from their surroundings.

This fusion, far from being harmonious, would resemble dissolution: the individual, deprived of the dynamic tension that defines them in relation to their environment, would lose the very essence of their identity.

Hypersensitivity as a Social Pathology

This cognitive fragilization finds an echo in hypersensitivity to discourses deemed offensive.

The PATURE study (2001–2019), conducted under the eponymous European contract, sheds light on this phenomenon through a medical analogy.

By demonstrating that minimal exposure to microbial agents increases allergies in children, the hygiene hypothesis reveals that avoiding external aggressions weakens the organism.

Similarly, Atkinson argues that « if we want to strengthen society against offensive discourses, we must allow their circulation.«

Thus, like childhood diseases, our resilience grows with exposure.

Criminalizing language—whether critical, sarcastic, or simply divergent—lowers the threshold of social resilience, transforming hypersensitivity into a collective pathology.

Against Censorship, the Robustness of Dialogue

In the face of discourses perceived as intolerant, the response lies not in censorship but in robust dialogue.

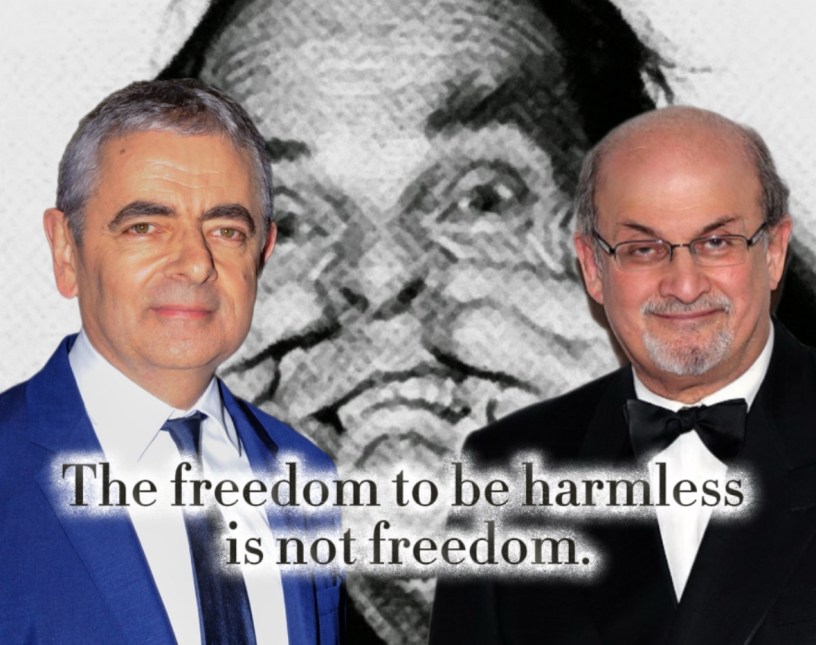

« The freedom to be inoffensive is not freedom ».

Atkinson adds: « If we want a strong society, we must encourage open debate, including the right to offend. »

Salman Rushdie has already denounced this « industry of indignation » which, under the guise of benevolence, establishes a form of authoritarianism.

Censors, claiming to be intolerant only of intolerance, substitute one orthodoxy for another, stifling the diversity of ideas.

A healthy society absorbs uncomfortable statements without resorting to repression.

Freedom of expression, including the right to offend, is essential to preserving the robustness of a democracy.

As Atkinson emphasizes, social resilience is not decreed: it is forged in the confrontation of ideas, not in their suppression.

Conclusion: For an Immunized, Not Sterilized Society

By sacralizing identity and criminalizing language, certain contemporary discourses, though driven by empathetic intentions, threaten the cognitive integrity of the human species.

They promote a fragile individual, exempt from adaptation, and a flaccid society incapable of advancing the perfection of the human mind by elevating the individual.

Yet, it is in the dynamic tension between the individual and their environment, between ideas and their contradictions, that progress and resilience are born.

For Atkinson, the term « resilience » applied to society should give way to « robustness » or « immunity. »

A robust society does not fear offense: it transforms it into fuel for vibrant debate, the guarantor of a humanity capable of reinventing and, above all, perfecting itself.