The official Rwandan narrative about the events leading up to the genocide has often been taken at face value by historians unfamiliar with information warfare and psychological operations.

Roméo Dallaire himself described Paul Kagame as a “master of psychological warfare,” highlighting his ability to exploit the psychological and logistical weaknesses of his enemies, particularly during the capture of Kigali.

Narratives: Weapons of Cognitive Warfare

On May 21, 2023, in Munich, the following slogan could be read on the giant screens overlooking the stage where the band Pink Floyd was performing: “Control the narrative, rule the world.”

We are indeed living in an era of narratives, stories that often lack objectivity in the selection of the elements that constitute their content and in their arrangement.

Every day, storytelling professionals from marketing, specialized military units, and certain social science departments construct narratives with creativity, ingenuity, science, and Machiavellianism, designed to deeply influence individuals’ cognition.

Storytelling is not a new phenomenon. Humanity has never stopped telling itself stories.

As the American philosopher Daniel Dennett writes, “We don’t play these stories; often, these stories play us.”

In the realm of influence, narratives are composed of “selected and arranged evidence not to attempt to approach the truth or aim to restore the facts, but to shape public perception,” with the goal of facilitating the achievement of predetermined objectives.

Thus, narratives have become weapons of cognitive warfare, sometimes aimed at strengthening the power of a group and/or undermining the strength of a nation.

What matters is that narratives supporting national interests, such as those of Paul Kagame’s regime, possess a minimum degree of credibility so that a simple journalistic analysis cannot easily undermine them.

Narratives designed to influence perceptions are crafted in the same way as so-called “prescriptive-normative” theories, which Thierry Ménissier, a philosophy professor, defines as “theories proposing a set of concepts credible enough to hope that they might shape humanity’s relationship with reality and enable political action.”

Narratives are therefore part of the deliverables designed within the framework of so-called psychological operations, which are part of broader influence strategies and, according to the U.S. military, consist of “influencing target audiences to support national objectives by conveying selected information and/or promoting actions likely to affect emotions, motivations, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behavior of foreign audiences.”

The challenge lies in distinguishing between narratives intended, on one hand, to fuel an influence war—what can be described as teleological, because they are designed to produce desirable effects aimed at shaping public perception to facilitate national interests—and, on the other hand, scientific narratives meant to come as close as possible to reality within the framework of correspondence theory.

Influence narratives will often advance covertly and may sometimes present themselves as scientific accounts, particularly when written by activist researchers or under an academic mercenary contract.

Paul Kagame and Psychological Warfare

Before leading the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), Paul Kagame served as deputy director of intelligence services in Uganda under Yoweri Museveni’s regime.

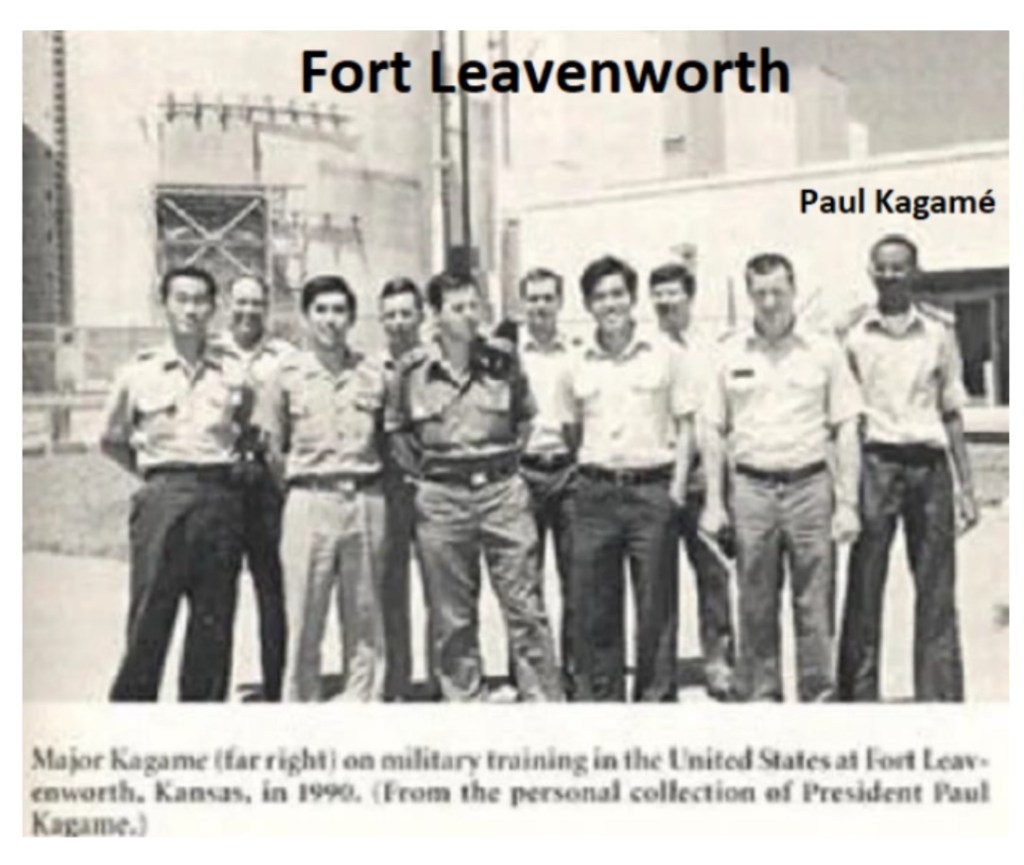

In 1990, he underwent training in the United States at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, where he was introduced to psychological operations.

Paul Kagame is even said to have declared:

“We used communications and information warfare better than anyone. We invented a new way of doing things.”

The Context of the Aggression Against Rwanda from Uganda (1990)

On October 1, 1990, an aggression against Rwanda was launched by Tutsi refugees who had settled in Uganda since the 1960s. These refugees had been recruited into the National Resistance Army (NRA) by Museveni, who relied on them to overthrow Milton Obote in 1986.

Under Uganda’s so-called “indigeneity” policy, these Tutsi refugees were integrated into the Ugandan military apparatus and trained in combat.

Paul Kagame, then deputy director of intelligence, was one of the key strategists of this operation.

Yet this invasion constituted a flagrant violation of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which stipulated in Article 23, paragraph 2:

“The States Parties undertake to prohibit:

a) any person enjoying the right of asylum from engaging in subversive activities against their country of origin;

b) their territories from being used as a base for subversive or terrorist activities against another State.”

Despite this clear violation of international law, the RPF, thanks to significant support from its diaspora and the United States, managed to present itself as a liberation army. Only France denounced this military aggression.

In contrast, the international community, under Anglo-Saxon influence, sided with the Tutsi rebels.

This aggression occurred in a climate of internal tensions.

The invasion took place against a backdrop of growing internal tensions in Rwanda: an economic crisis due to the collapse of coffee prices, the country’s main resource, and political unrest against the authoritarian regime in power.

From the very first days of the attack, the Rwandan army (FAR), composed almost exclusively of Hutus, was deployed to contain the RPF’s advance. Poorly prepared and understaffed (initially between 5,000 and 10,000 men), the FAR had to quickly reorganize:

A massive recruitment drive, accompanied by accelerated training—often limited to learning how to handle individual weapons—increased their numbers to 35,000 by 1994.

At the same time, the Rwandan government immediately equated the RPF attack with an internal threat, accusing the Tutsi population living in Rwanda of forming a fifth column.

Although the RPF benefited from discreet support from some Tutsis and Hutu opponents—some of whom provided crucial intelligence on the positions of the Rwandan Armed Forces, as confirmed by General Dallaire’s reports, which highlighted how the RPF exploited these internal divisions—the Rwandan response was often indiscriminate.

Thus, as early as October 1990, around 10,000 Tutsis and Hutu opponents were arrested to prevent the emergence of an internal “fifth column.”

The regime instrumentalized the media, particularly radio, to reinforce the idea that the RPF was a foreign force backed by Uganda—which, in this case, was true.

In hindsight, it would become clear that the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and their Ugandan proxy indeed played a key role in supporting the RPF.

In this regard, Major-General Roméo Dallaire would write in his book:

“If I had been even slightly suspicious, I could have established a link between the Americans’ obstructive stance and the RPF’s refusal to accept a larger UNAMIR 2.

In the period leading up to the war, the military attaché from the U.S. embassy was regularly seen traveling to Mulindi (the RPF base).”

The Fear of a Return to Tutsi Domination

The civil self-defense strategy was fueled by the fear of a return to Tutsi domination similar to that before 1959.

After the genocide, Dallaire would write: “Who, exactly, had been pulling the strings throughout the campaign?

I sank into dark thoughts, wondering if the campaign and the genocide hadn’t been orchestrated for a return to the pre-1959 status quo in Rwanda, a time when the Tutsis ruled everything.”

This fear was thus relatively easy to instill, as it was not without foundation.

Indeed, in 1957, Grégoire Kayibanda, leader of the Hutu movement, wrote the Hutu Manifesto, in which he demanded:

The abolition of indirect administration that favored the Tutsis;

Equitable access to civil service positions;

Recognition of individual land ownership.

The Tutsi elites’ response to these demands was unequivocal:

“The Bahutu and we (the Batutsi) have always been in a relationship of servitude. There is therefore no basis for fraternity between them and us.” (12 Bagaragu b’Ibwami, 1958)

Faced with this categorical refusal of any reform, the 1959 revolution was marked by interethnic violence, leading to the exile of many Tutsis to neighboring countries, where they formed influential networks.

Some were not fleeing only for their safety but also because they found it inconceivable to lose their superiority.

It was in this context that, starting from October 1, 1990—the date of the RPF’s territorial aggression—the idea of a fifth column took root in the minds of many Hutus, facilitating adherence to propaganda accusing the Tutsis of preparing a return to their historical dominance.

Two major events reinforced this perception:

The Assassination of Melchior Ndadaye (Hutu President of Burundi)

A moderate, he had accepted a power-sharing arrangement.

His assassination by Burundian Tutsi soldiers led to the belief that Tutsis would never tolerate any compromise.

On July 10, 1993, Melchior Ndadaye became the first democratically elected Hutu president of Burundi, a country marked by decades of domination by the Tutsi minority (15% of the population) and by a genocide in 1972 that decimated the Hutu elite (120,000 victims)[1].

He sought to promote a policy of national reconciliation by appointing a Tutsi prime minister, Sylvie Kinigi.

Thus, what was prepared after the territorial aggression of October 1, 1990, was not the genocide itself, but a civil self-defense program that spiraled out of control, resulting in the systematic elimination of anyone suspected of sympathizing with the RPF, with the irrefutable presumption that Rwandan Tutsis were necessarily potential allies of the Tutsis from Uganda.

Through this symbolic gesture of including the Tutsi minority in the government, he aimed to demonstrate his desire to overcome ethnic divisions.

On October 21, 1993—just 102 days after his inauguration—he was executed in a military camp by Tutsis from the army.

His assassination by Burundian Tutsi soldiers sparked mistrust, making political actors particularly cautious about engaging with the RPF and opposition parties.

Thus, the Burundian context lent credence to the idea that it was difficult to trust the RPF and that it aimed, as in Burundi, to restore historical Tutsi domination.

The January 21, 1993 Attack and Massacres of Civilians by the RPF

Between October 1, 1990—the date of the RPF’s territorial aggression from Uganda—and January 21, 1993, reprisals following RPF attacks caused, according to a Human Rights Watch report, approximately 2,000 Tutsi deaths, or 74 deaths per month.

On February 8, 1993, the RPF launched a major offensive, violating the ceasefire in place. This offensive, conducted in the Byumba and Ruhengeri regions, achieved significant military successes.

The RPF justified this action as necessary to stop the massacres of Tutsis and to unblock negotiations hindered by the Habyarimana regime.

However, analyses suggest the real objective was to strengthen their military and political position.

The humanitarian consequences were disastrous.

The offensive displaced about one million people, mostly Hutu civilians, who took refuge around Kigali, and resulted in the deaths of 40,000 civilians, overwhelmingly Hutus.

According to René Lemarchand, the majority of the Interahamwe were recruited from “internally displaced persons,” that is, Hutus displaced as a result of the “small” Burundian genocide of 1972 and the RPF attacks since 1990.

Massacres were perpetrated by the RPF in several localities, notably in Ruhengeri and Byumba.

The RPF was accused of crimes against humanity, including civilian executions, destruction of infrastructure, and acts of terror against the population.

This offensive allowed the RPF to weaken the government coalition, seize a significant portion of the Rwandan Armed Forces’ (FAR) military equipment, and strengthen its position in negotiations.

It also exacerbated the country’s political and military polarization, weakening moderate Hutus who supported dialogue with the RPF.

Several witnesses, including officers and international observers, reported atrocities committed by the RPF during this period.

In summary, the February 1993 offensive had devastating consequences for the civilian population.

It heightened ethnic and political tensions, reinforced the belief that the RPF posed a danger to Hutus, and contributed to the dynamics that led to the genocide.

Toward Total War

By the dawn of the April 6, 1994, attack, the atmosphere was explosive.

The fifth column thesis was firmly entrenched in people’s minds, as was the conviction that the RPF sought absolute power, a prelude to a Tutsi domination reminiscent of pre-1959.

Since the territorial aggression of October 1, 1990, Paul Kagame had worked to radicalize some so-called “moderate” Hutus to discredit them, thereby capitalizing on the absence of credible interlocutors and the Rwandan government’s unwillingness to negotiate.

He employed a strategy similar to that of Benjamin Netanyahu, which involved fostering the rise of Hamas to weaken the Palestinian Authority.

Acting as a pyromaniac firefighter, Kagame stoked tensions to advance his cause but to the detriment of Rwandan Tutsis.

In response, propaganda immediately mobilized the Hutu population, while the regime organized paramilitary groups like the Interahamwe, tasked with preparing the civil self-defense program.

The trigger for the genocide was the attack on the plane carrying two Hutu presidents, an act that several reports, including the Hourigan report, attributed to the RPF.

Four days before this event, Paul Kagame made prophetic remarks to Major-General Dallaire, who recounted them in his book:

“I had never seen him so somber. He simply added that we were on the brink of a cataclysm and that, once triggered, no means would be able to control it.”

Ultimately, the genocide against Tutsis and Hutus accused of collaborating with the RPF was part of a civil self-defense strategy in which the ends justified the most atrocious means.

Testimony of an Expert

The leading expert witness at the ICTR, Alison Des Forges, testified before the ICTR Appeals Chamber as follows:

“While clearly seeing the existence of a plan, I have no way, no means, of establishing that the people who participated in this plan intended to commit genocide and to…”

“In fact, I even assume that some did not have that intention.

Question: So, Madam, you believe that people could have participated in the planning of the genocide unintentionally; is that correct?

Response: Except in the sense that I would not say that those who participated without the intention of committing genocide were people participating in a genocidal plan.

Because, if we are to examine the characteristics for defining this crime, there must be a conscious intent on the part of the participants or perpetrators.

And so, I would not draw that kind of conclusion; I would rather say that these were people—or that it’s possible they were people—who participated in planning a civil self-defense program before April 6, and whose intention was not necessarily to commit genocide.

Because I have no way of knowing or proving that each of these individuals had genocidal intent.”

The result was the elimination of over 80% of Rwanda’s Tutsis—that is, the commission of a genocide against the Tutsis, systematically, given a presumption of complicity deemed irrefutable—as well as Hutus suspected of collaboration.

- EuroMaïdan : Comment le couple EU-US a semé les graines de la Guerre en Ukraine

- La Transformation Idéologique des Recrues Banyamulenge : Des Techniques d’Effondrement Psychologique à l’Implantation d’une Dichotomie Victime potentielle -Génocidaire potentiel

- L’absence d’intérêt stratégique pour les extrémistes hutu dans l’assassinat du président Habyarimana, et l’intérêt stratégique majeur d’un tel acte pour le FPR

- L’industrie rwandaise des faux témoignages au service de la neutralisation et de la spoliation de l’ancienne élite habyarimanienne.

- RÉCIT D’UNE MANIPULATION (15.07.2017)